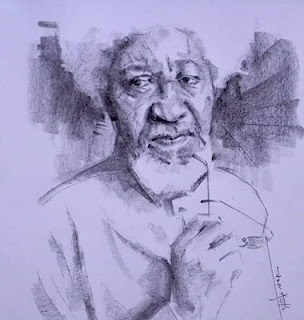

Wole Soyinka and the Logic of a Democratic Ideal in a Postcolonial State By Prof. James Tar Tsaaior

Wole Soyinka is a study in exceptionalism. His exceptionalism as

Nigeria/Africa’s Nobel laureate is only equaled by a few Nigerians. Emeka Anyaoku,

for instance as Commonwealth Secretary-General, the late Chinua Achebe, his

fellow writer as the most read African novelist. Soyinka is also known globally

for his writings and political activism. However, his literary practice has

always come under intense interrogation by the critical establishment

especially the formation that identifies the lack of a clear, unambiguous

political dimension to his oeuvre.

In its discursive elaborations, this critical collective accuses

the Nobelist of investing enormous agency and epistemological capital in the

lone, individual figure who imposes on himself the exclusive preserve of

galvanizing society in the kinesis of history. Inevitably, the mass of the

collectivity and their communal aspirations and energies for the revolutionary

transformation of the patterns of social and cultural production are

subsidiarised to the will of the larger-than-life hero. Whether it is in his

dramaturgy or poetic output, this critical intellection has become definitive

of the attempts to come to grips with Soyinka’s writings.

The critical charge is that Soyinka is enamoured of lone,

individual subjectivities who impose the communal will upon themselves and

embody history without due recourse to the mass of the people who are the authentic

creators of history may be somewhat compelling. However, to pronounce Soyinka

guilty and to convict him of ahistoricity is to carry one’s luck too far.

Allied to this assumed deficit in apprehending the networks of historical

knowledge is the equally perennial accusation that Soyinka’s artistry does not

pursue progressive themes that are dialectical and materialist in character.

This too looks like training the arrow against a pin which is likely to be

missed.

This supposed absence of a progressive centre and ideological

gravitation to progressive possibilities in Soyinka’s poetics thus becomes the

overriding and informing concern which drives this interpretive current.

Interestingly, Nigeria’s present postcolonial contradictions issue directly

from this lack of a progressive vein in her politics, economics and culture. A

culture of elitist predation, oppression, exploitation and corruption has been

entrenched and celebrated as national pastime since independence in October

1960.

The critical skirmish concerning Soyinka strikes at the very

core of discourses which exist at the interface of the formalist and

functionalist approaches to literature and art: the autonomy of art as a

self-sufficient, aesthetic creation and its social/political functionality. I,

however, argue that Soyinka has always been a politically active and positioned

writer and that critical perspectives which negate this reality have neither

been charitable nor able to transcend the concrete dynamic of his art.

Indeed, not to appear to have

a clear political/ideological sympathy is itself a political rite. While it may

be somewhat difficult to delineate the fine details of the political lineaments

inherent in Soyinka’s creative writings, his essays constitute a more

crystallizing agent in the determination of his ideological intentions which

are thinly disguised in his creative sensibility. For instance, his collection

of essays, The Open Sore of a Continent contextualizes

and exemplifies Soyinka’s political activism as a writer.

One of the most vociferous and unsparing of the critics has been

Femi Osofisan who has interrogated Soyinka’s idealization and deification of

the lone, promethean individual who bears the burdens of history and takes on

the forces of society to the mutual exclusivity of the collectivity. Valorizing

a Marxist consciousness, Osofisan denounces Soyinka’s lack of recourse to clear

ideological mooring of his aesthetics in a collectivizing partisanship that

foregrounds and takes sides with the mass of the people and makes them the true

agents and subjectivities of history. Osofisan is particularly disturbed by

Soyinka’s deployment of animist metaphysics and the individual Promethean

protagonist theorized in Aristotelian poetics.

But Osofisan is not

alone. Biodun Jeyifo has also engaged in critical skirmishes with Soyinka’s oeuvre especially his dramaturgy and identified

its ideological limitations in elitist aesthetics. Jeyifo has deconstructed

Soyinka’s poetics based on his appropriation of cultural idioms and mythic knowledge

grids without fully acknowledging the functional role of the community as

veritable makers of history. His grouse pendulates between Soyinka’s

ahistoricism and lack of historical dialecticism especially concerning the

latter’s creative daemon, Ogun.

Jeyifo, therefore, rails Soyinka for literary idealization and

for lacking true revolutionary potential. At the interface of the two

deconstructive appraisals of Soyinka’s poetics, Promethean individualism and

the lack of dialectics of historicity are the animating concerns. Tejumola

Olaniyan pursues the argument in the same direction of the individuation of

history and its currents as hypostasised in the lone figure. Related to this

also is the subsidiarisation of the female principle to patriarchal power

structures in the gender politics that define the African cultural cartography

where women are rendered invisible and voiceless as manifested in the

thematisation of the god, Ogun.

It is ironic that Soyinka

is himself on the firing range concerning the cultural politics of Negritude of

which he has been a fierce critic. He is known to have famously characterised

the movement (with its arch-exponents such as Leopold Sedar Senghor, Aime

Cesaire and Leon Damas) as a tiger which does not need to proclaim its tigritude

but act it. What Soyinka perhaps does not appreciate is that before the leopard

can pounce, it must declare itself through its growls. The nativist

intellection of the bolekajatriumvirate of

Chinweizu, Onwuchekwa Jemie and Ihechukwu Madubuike has also been at the

receiving end of Soyinka’s polemics and rehearsed vitriol. Many of the critics,

however, have increasingly interrogated the fidelity of Soyinka’s cultural

politics to Africa, the home continent he claims to strenuously defend in his

literary and critical practice. READ MORE AT STORRIED.COM

James Tar Tsaaior, PhD

Professor of Media and Cultural

Communication,

School of Media and

Communication,

Pan-Atlantic University, Lagos

Comments

Post a Comment